Chymica Vannus: when Alchemy’s history is not enough to explain a title not to be taken for granted. Just assonance with the Mystica Vannus Iacchi?

Believe it or not, I have neither read the influential Verginelli translation nor the Donatino Domini’s. So I’m virginally facing the task. I will go on my own, aware of the risk and burden. So expect an awful and unhurried style. Of course, discrepancies will be found by readers already familiar with other translations. I have to warn them that I will translate just the most outstanding parts and summarize the other cases, as usual. Trust me, I can assure you the Chymica Vannus integral reading may result in pompous, redundant, and pretty labyrinthine at times. The translation turns struggling from the very beginning, the frontispiece.

Chymica Vannus was unique in the alchemical panorama. Always defined as a strange book, it is actually unusual, different, and more creative ( and learned, in my opinion) than the usual trend of alchemical books of its era, and not only. As an independent researcher, I can try to translate it without excessive anxieties and fears of breaking (hermetic and marketing) taboos.

The first point to make is that the author doesn’t mention himself. Nevertheless, we shouldn’t feel the need to. This book is a “per se” work. We shouldn’t need to increase or decrease its value searching for the author’s trustworthiness. But, as we know, people love to read the author and not the book (when they read). So this book does not escape the rule of the outstanding alchemical works of uncertain authors: if an originator can not be inferred, he can always be invented. I fail to understand why and how Chymica Vannus could be attributed to Thomas Vaughan by some modern historians, perhaps because of the assonance with Vaughan of some topics in the book.

Even though, on page 7 of the book, we can find the second sentence the author uses to explain the origins of his work ( we will see the first one, mentioned by Ferguson, in some paragraphs below): “… & à me Londini in Anglia è germanismo in latinum transfusus est…”, and through me, Londoner in England from Germanism in latin has been moved…. (referring to Pharmaco Catholico). Nevertheless, we can affirm there is no evidence of Vaughan’s involvement in the work. This bare sentence cannot be taken by a serious researcher as identification evidence.

Even more arbitrary is the attribution by Stanislas de Guaita (as far as an attribution by de Guaita is worth being seriously taken into consideration), whose imagination galloped wildly over the line mentioned above. According to him, the mere translation from German to latin made this book be attributed to the Brothers of the Rose + Cross. And the author certainly was Philalethes, Grand Master of the R + C. Of course; these nineteenth-century fellows belonged to secret self-proclaimed brotherhoods, for whom pieces of evidence were inconsequential.

Every person with a decent knowledge of Latin can notice a big difference in literary style between Introitus Apertus and Chymica Vannus. There are only two features in common: we can hardly find any syntax errors, and both authors’ knowledge of the Latin language’s double meanings is astonishing. They don’t write in latin; they teach latin. These two books were both written by tremendously learned writers. But they are temperamentally different. Cold and almost merciless, Philalethes. Intense till arousing pity, Chymica Vannus author. The first one is boldly confident. The second is desperately conscious of being alone.

If Chymica Vannus must be given a particular author, some severe pieces of evidence head to J. de Monte Snyder instead. This is also Ferguson’s opinion in his Bibliotheca Chemica. About Monte Snyder, we don’t even know his first name. In some publications, we can find John; in others, Johannes, and in further, even Joseph. So I prefer, like Ferguson, to use the first letter J, on which at least all historians seem to agree.

The most comprehensive details on his biography were provided by the same Ferguson: “Did J. de Monte Snyder write Chymica Vannus or translate it or simply edit it? No other known version of it exists… Of the Author, nothing is known except what he says incidentally, as in the little of the Commentatio, that he translated it from the German when he happened to be in London, or in the ‘Epigramma in Zoilium’ when he says: ‘Gelria mi patria est, sed Venloa propria terra, me mihi scito data non sine lege loqui. Schmieder says that though apparently Dutch, his name was Mondschneider, and he was a native of the (German) Palatinate. Others say that Monte Snyder was a grandson of Levinus Lemnius on the mother’s side and from him got the tincture with which he performed several transmutations. One of the most notable of these was narrated by Vreeswyk, and from him, the narrative was copied by other writers. It took place at Aix-la-Chapelle in 1667, in the presence of Guillaume, a goldsmith and assayer, and Monte Snyder, on that occasion, produced gold of extraordinarily fine quality from lead and copper. After his stock of “tincture” was exhausted, he is said to have died at Mains in poverty”.

The last information, in my humble opinion, gives an aura to Monte Snyder. In fact, I don’t understand why and how an alchemist should grow rich in Alchemy, letting aside the forbidden practice of producing gold and the other, forbidden by good taste, of cash on books.

Another attribution has been given to Willielmus de Roe. In fact, in a manuscript in the British Library, the name ‘Willielmus de Roe’ is written “This was the author of the book, Chymica Vannus, printed in Holland, 1666”.

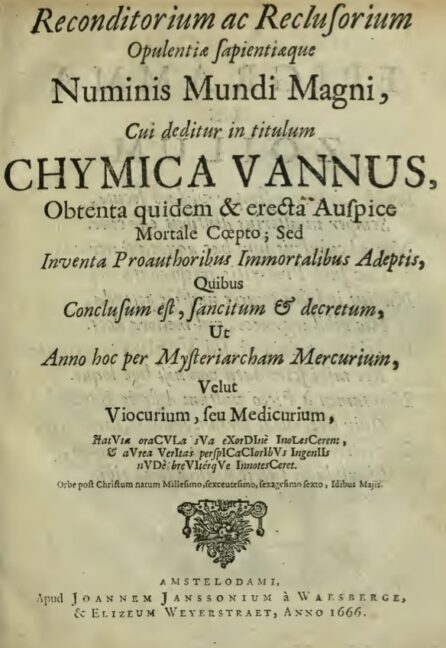

But let’s get to Chymica Vannus frontispiece translation now, just after the first engraving, entitled Character Adeptorum, which I will present in another category. So:

RECONDITORIUM AC RECLUSORIUM Opulentiae Sapientiaeque NUMINIS MUNDI MAGNI, Cui deditur in titulum CHYMICA VANNUS, Obtenta quidem et erecta Auspice Mortale Coepto; Sed Inventa Proauthoribus Immortalibus Adeptis, Quibus Conclusum est, sancitum & decretum, Ut Anno hoc per Mysteriarcham Mercurium, Velut Viocurium, sed Medicurium, Velut StatVta oraCVla sVa eXorDInè InoLesCerent, & aVrea VerItas perspICaCIorIbVs IngenIIs nVDe breVIterqVE InnotesCeret (Statuta oracula sua ex ordine inolescerent, & aurea Veritas perspicacioribus ingeniis nudè breviterque innotesceret).

Orbe post Christum natum Millesimo, sexcentesimo, sexagesimo sexto, Idibus Majis. Apud Joannem Janssonium à Waesberge, & Elizeum Weyerstraet, Anno 1666.

My verbatim, as far as possible, translation:

REPOSITORY (1) and HIDDEN TREASURY (2) of the Power and Knowledge of the SUPREME APPARATUS (3) NUMEN (4), which is dropped in the title CHEMICAL WINNOWING FAN (5), At the beginning still obtained and constructed under mortal auspice; but discovered under the patronage of the victorious (6) immortal authors (7), Through who is concluded, ordained and heralded, in this period by means of Mercurius presiding over the Mysteries (8) as well as Expert path (9), so (10) the healing Mercurius (11), may their firm predictions be developed according to the order and the golden truth be made simply and concisely known to discerning minds.

In the world after Christ was born, thousandth, six hundredth, sixtieth, sixth, Ides of May. Amsterdam by Johannes Jansson from Waesberg and Elizeus Weyerstraet, the year 1666.< Let’s analyze some double-meaning terms:

- Reconditorium derives from the substantive Reconditor, meaning “who stores, keeps, gets hold”. Conditor ” author, teller”. Reconditorium means “repository”, but it was often used, as well as Conditorium, as ” coffin, sarcophagus, tomb, urn for ashes”. For instance, Suetonius used “conditorium” recalling Alexander the Great’s sarcophagus worshipped by Augustus: … conditorium et corpus Alexandri Magni “, while the more recent French author Mabillion: the saint’s altar ” … Santii reconditorium… ;

- Reclusorium derives from the verb recludo, to open, dig up, unveil, discover, to close, close, store”. Reclusorium was used during the Middle Ages to mean monastery, ” reclusorium intravit” for “she enters monastery”. Also, sometimes it has been confused with “Exclusorium, means hidden treasury;

- Mundus might not be easily translated as “world”, as a neo-latin could rush to do. In fact, the first translation from latin is “equipment”, or “set of tools”; the second is “world” as globe;

- Latin Numen: will, command, numen, divine power, divine majesty;

- Vannus is one of the rare latin feminine substantive looking like masculine (-us), requiring a feminine adjective. Chymica means ” chemical”. The word “Vannus” meaning will be a major object of the second part of this article.

- Adeptis is the perfect participle of the verb ădĭpiscor, to accomplish-successfully achieved. In latin, adeptis means neither expert, experienced, skilled, as in English, nor follower as in Italian, but victorious, winning;

- The form “author” is a neologism, the ancient latin being auctor;

- Mysteriarcham seems a derivation from Mystērĭarchēs, which means “the one who presides over the mysteries”;

- Literally, “Roads Inspectors”. Of course, being an Alchemy book, these roads cannot but refer to alchemical paths or ways;

- Sed is a latin conjunction with conflicting meanings, clearer for an English mother tongue, less for a neo-latin: It can stand for so, also, but, nevertheless, and except;

- Medicurius: from “Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne; ou, Histoire, partie mythologique …“, Paris 1833, Volume 55 page 42. By Joseph Fr. Michaud, Louis Gabriel Michaud: “Medicurius, mercure. Ce fut, dit-on, son premier nom. La paronomasie des deux mots (medicuria, mercurius) a seule pu engager à èmettre cette opinion”. Or, Medicurius, Mercury. It was said to be its first name. The paronomasia of the two words (medicuria, Mercurius) was able to issue this opinion.

Let’s try to analyze the entire header now:

The phrase “cui deditur in titulum”, which is dropped in the title, could make us undervalue all the remaining parts as baroque decorations. In fact, many tend to abandon the reading just after the visual achievement of that “Chymica Vannus”, which may seem so clearly a “passing through the sieve of chemistry”, or separating coarser from finer. In fact, sieves were indispensable devices in ancient chemistry. But in this case, the term “cribrum” should have been used instead.

A vannus is not a cribrum. A vannus–winnowing fan is not a filtering device but a separating one through the action of air currents. A van is a broad basket, o oar, into which the corn, or rice, after being trashed, is thrown in the direction of the wind to let deposit corn and chaff in different places. In archaic times it was also called bird’s wing. In this case, a sense of “discernment of the good from the evil, the real from the false” may be applied.

Johannes Jansson and Elizeus Weyerstraet published another book in 1737 ( perhaps their sons) with a “vannus” in the title. Precisely “Critica Vannus”, by Jacques Philippe d’ Orville, in which ancient philosophical excerpts were explained, condensed, and syndicated. The book is a classic philosophical dispute in which one refutes or answers refutations. So, in this case, a clear concept of vannus as a scrutiny device may be applied at first sight. The detail is: by ancient Romans, did the idea of “Vannus” suggest a separating concept? Or an air current concept, instead?

This is not a pointless issue, since winnowing fans, besides agriculture, took an important role also in the ancient symbolism of mysteries. Virgilius, in his Georgics, describes many agricultural tools used in mythological symbolism. Among them is the Vannus winnowing fan. In fact, as we will see in a coming article on a Pompeii series of frescoes, the winnowing basket sacred to Dionysus is painted in the central part of a mystery initiation scene (1). The liturgical name of the object was ” Mystica Vannus”, or the mystical winnowing fan. To be more precise, the full title was ” Mystica Vannus Iacchi”, or the mystical winnowing fan belonging to Iacchus, a hieratic form of Bacchus. That’s to say the Greek god Dionysus (2), the divinity entrusted ( with Demeter and Persephone) with mortal-immortal secret rites. So, should we give “Vannus” a “passing through scrutiny” meaning? Or might this just be a modern and unlearned conjecture?

Those who have hurried over the Chymica Vannus long title may not have pointed on “Obtenta quidem et erecta Auspice Mortale Coepto; Sed Inventa Proauthoribus Immortalibus Adeptis…”, or “At the beginning still obtained and constructed under mortal auspice; but discovered under the patronage of the victorious immortal authors. Through who is concluded, ordained, and proclaimed, may their firm predictions be developed according to the order”.

Doubts could be strengthened when bumping into the phrase word. Mysteriarcham Mercurium”. As said in the previous page, Mystērĭarchēs means “the one who presides over the mysteries”, in ancient roman times not intended as something that is difficult or impossible to understand or explain, but the one presiding over the secret rites of life and death, to which only initiates were admitted.

Fascinating is the combination of Medicine and Mercurius in the paronomasia “Medicurius” ( see point 11). Mercurius is both the Roman divinity for Hermes and our Secret Fire/Spirit of life. Alchemically speaking, there is no difference between these two. Of course, this humanized god was just an allegory. Chymica Vannus’s author, by a minimal margin, intended just the allegory and not the hidden signification. In fact, it is expected a particular time of the year ( and not all years) in which, through this presiding Spirit, the rite will be accomplished.

Might this particular date be the mentioned one, that’s to say ides of May of a specific year? If not, why repeat the year just a line above the book publishing date? Ides was a fluctuating middle of May (3). Concerning the year, don’t be scared by this 1-666. There are no evil numbers here. In Alchemy, there are no plans for it. But for something which can be accomplished after the sixth of the sixth. In fact, the alchemical “Week of the Week”, which incidentally may occur in the middle of May, should last six days, and on the seventh, a feast will take place (4).

I forgot to mention that our Mercurius is also an expert on roads or paths. Chymica Vannus, the author, is keen to tell us further we are not before our healing Mercurius. Probably the path chosen this time is not that of our common works to achieve our alchemical medicine or the work’s on minerals final result ( see an Opus Magnum scheme), but something really more dangerous and forbidden.

The reasons why the “StatVta oraCVla sVa eXorDInè InoLesCerent…” line presents strange capitals are out of my comprehension. Anyway, a similar construction was not unusual in epigraphic Latin.

P.S.: Today, September 17th, I bought the translation by Virginelli. One remark I have to make to the translators is the clear specification of 15th May as ides of May. As I said in my article in footnote 2 ides fall just roughly in the middle of each month: “In their origin, Roman people, as most of the ancient people, used a lunar calendar in which a month corresponded to a lunation. They did not count the days from the beginning of the month: 1 2 3 4 etc.., but counted the days until the calendae, idus, or nonae, depending on which of them were closer, as when counting the days until an important event, in the short countdown. The first day of the month was the “calendae” or the first day of the new moon, the “nonae” was an intermediate between the new moon and the “Idus”, or the full moon, that’s to say, nine days to a full moon”.

In fact, this ides of May might represent a date much more interesting than the mere publication of the book as we will see in the following work.

To be Continued.